Nearly every web browser has a built-in private browsing feature. During normal browsing, all of your web activity is stored locally on your machine, including website history, cookies, and cached data. Sometimes people don’t want to leave a log of their browsing history, so luckily all the most popular web browsers include a feature to make this simple. But how effective is the private browsing feature?

How Private Browsing Works

Now, you could just go and manually remove your browsing history yourself, but as we know, deleting something on a computer doesn’t truly delete it. The files that hold all of this data can still be easily recovered through techniques like file carving. So, the most effective way to prevent this is to make it so that this data is never written to the disk in the first place. This is what the private browsing features aims to do. The idea is that while you have private browsing enabled, all your browsing data will only be stored in RAM, and never written to the disk. This way, when you close the browser, all the data is gone. If nothing is ever written to the disk, then there is nothing to be recovered.

Is It Effective?

The idea sounds good, but you might ask how effective it really is in practice. Most browsers will do a good job at not writing any explicit history logs to the disk, but there is a whole lot of other data the computer works with that needs to be considered. When you visit a website, the browser also needs to download all the resources on the page so it can display it. This data is stored in the browser cache and is composed of HTML files, pictures, and web scripts. Even when private browsing is enabled, it is not at all unusual for the browser to still temporarily write these files to the disk and then immediately delete them after the session is done. When this happens, these files can now be recovered if they weren’t effectively overwritten. I decided to test out how effective different browsers are with this, so I created a virtual machine and installed Microsoft Edge, Mozilla Firefox, and Google Chrome on them to see if I could recover any browsing history done through the private browsing feature.

Microsoft Edge

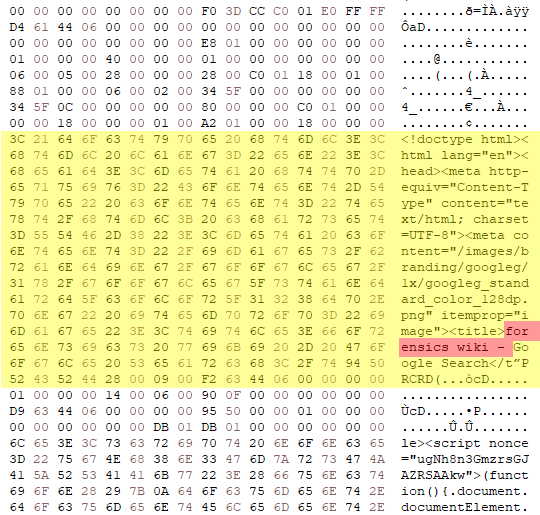

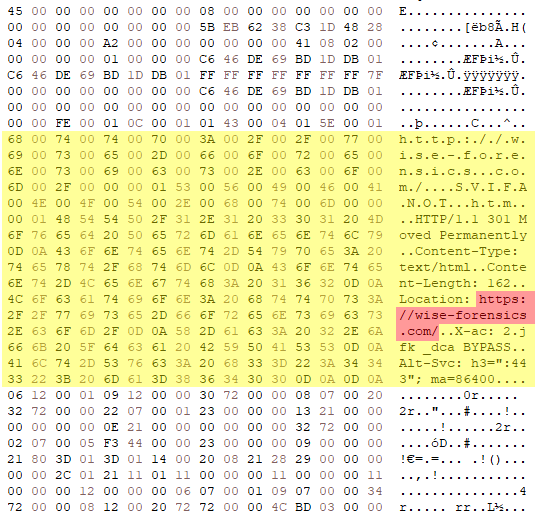

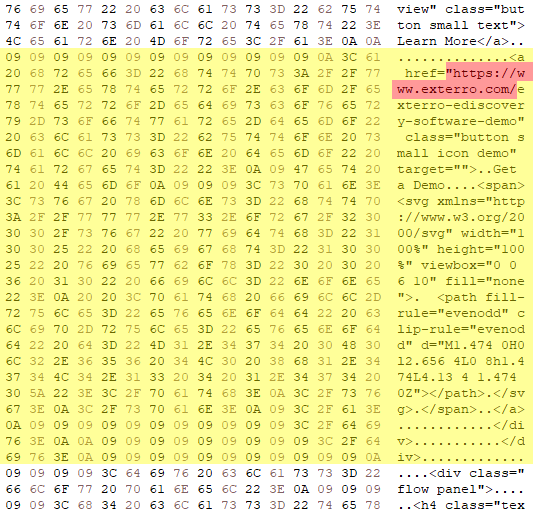

While using the private browsing feature in Microsoft Edge, I visited three different websites: forensics.wiki, wise-forensics.com, and exterro.com. Afterward, I took a disk image of the virtual machine and loaded it into a hex editor to see if I could find any remnants of these visits. It seems that Microsoft Edge leaves a lot left over, because I was able to find fragments of all of these visits in unallocated space.

Firefox and Chrome

Firefox and Chrome were a lot more effective on not leaving remnants of private browsing behind. After using the private browsing features of these browsers, I analyzed the disk image in a hex editor again, and I wasn’t able to find any traces of my browsing history in unallocated space. This could be a for a number of reasons. Firefox and Chrome might do a better job at ensuring everything, including the cache, truly stays in RAM during browsing. It’s also possible that these browsers utilize more effective data overwriting practices to this data after the browser is closed.

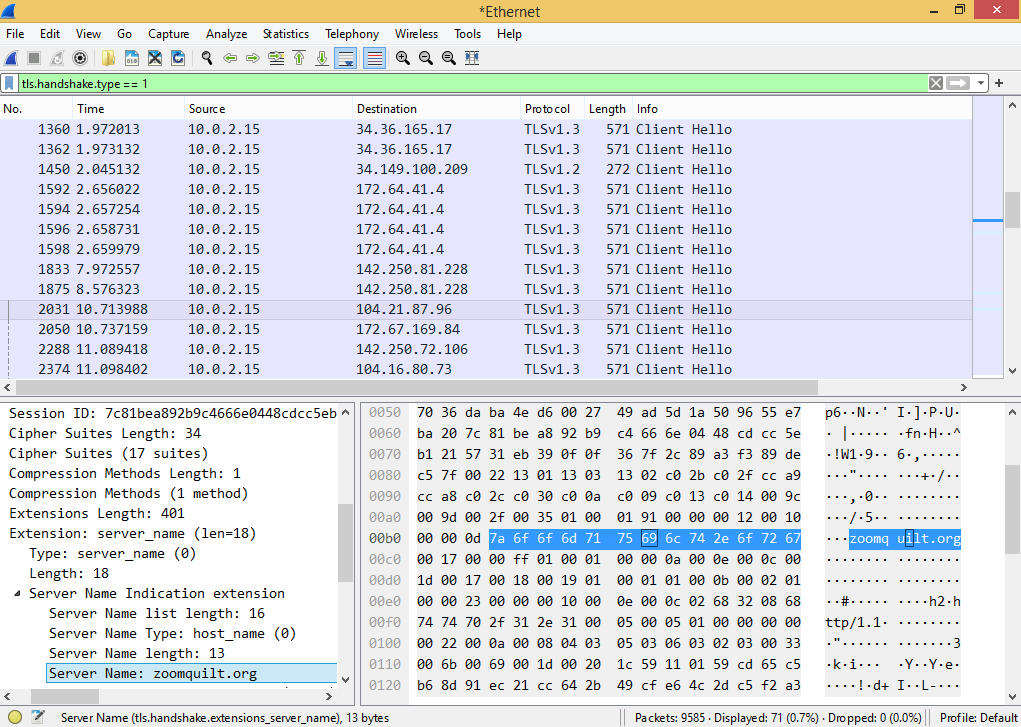

However, even in scenarios where there is genuinely no browsing data left behind locally, this doesn’t mean that there is no way for it to be recovered. The data will still exist over the network. When a user visits most websites, their web traffic will be encrypted with HTTPS, but not all of it is encrypted. Some metadata remains unencrypted because it needs to be routed properly. One key element of this metadata includes the name of the website which is exchanged during the TLS handshake. To demonstrate this, I ran Wireshark (a network sniffing software) on the virtual machine visiting zoomquilt.org through the private browsing feature. I’ve filtered the Wireshark output to only show the TLS protocol to make it easier to navigate. This shows a network log from my visits to each website.

So, while private browsing does make internet history more difficult to recover, like most data, it is not truly gone.

Leave a comment